Well, it was a busy 2025, but that’s no excuse. So here it is. On 19 February 2025, I was honoured to take part in an inaugural lecture showcase for the University of St Andrews Business School, alongside my colleagues Professors Alina baluch, Shiona Chillas and Ian Smith. We were introduced by the Principal, Professor Dame Sally Mapstone, while Dean of Arts Professor Catherine O’Leary was our MC. A very special, happy event, followed by a dinner in Upper College Hall.

The lecture has since been published as a commentary piece – and call to action – in the Journal of Cultural Economy, which I edit. It’s open access, available here or as a PDF.

For those who prefer, here’s the text and a few pictures:

“The times they are a-changin’: markets after neoliberalism, and how to study them”

You will doubtless know that it is possible, in the run up to Christmas each year, to take a day trip to see Santa Claus in his cottage in Lapland.[i] You and your children hop on an aeroplane and over the next few hours you are transported into a magical world of snowy forests, sleighs, and reindeer – not to mention merchandising opportunities – until, much later that day, you tumble back into Birmingham, Manchester or Gatwick, pockets empty but memories overflowing.

If you believe in Santa, you should probably stop listening now. For this particular market, offering an authentic Santa experience, is an enormously complicated organisational achievement. A network of local operators serves it: the husky tours, snowmobile transport, hotel and gift shop, buses, and the other paraphernalia of tourism. The actors playing Santa are recruited in the UK so that they will be familiar with the latest trends of the toy market and responsive to the vernacular demands of their small visitors. Authenticity is key, lest the visitors complain (again) about ‘a posh English Santa with a false beard.’

The whole is immaculately choreographed. Tourists take a sleigh ride across the frozen lake into the torchlit forest. Elves shepherd them into the cottage for a carefully scripted four-minute encounter with the man himself, out again into the sleigh, and back through the forest, tears in their eyes at the whole magical performance. Some days two flights arrive from different airports. On those days there are two Santas at work, hidden in different locations in the wood, managed by different circuits of elves, the passengers themselves identified by coloured badges on the lapels.

The fact that the elves have walkie-talkies seems not to spoil the Christmas magic. Nor does the queueing system, which relies on pens and printouts because it is too cold to use a battery device. We all know, from our own childhoods, that Rudolph demands a carrot. But reindeer do not eat carrots, so the handlers tell the tourists that reindeer cannot eat while they are working, lest they get indigestion. The carrots are left for the reindeer to ‘enjoy later’ and are re-bagged and resold. One year the lake did not freeze, and the sleigh could not get to Santa’s cottage; in haste, he was relocated to a shipping container and met the tourists there. Santa should not live like this, said the reviews.

What is going on here? How can grown adults be reduced to tears of joy by a sleigh ride through a forest to a cottage where they are checked in by an elf with a ring-binder (who they surely know is a student working a Christmas job), to meet, for a specified and scripted conversation, another actor who happens to have a bushy white beard and a jolly voice? Certainly there is more at work than the supply of Santa experiences meeting demand.

The crucial point is that markets are organized. They are practical achievements. As Teea Palo, Katy Mason and I show in our study (Palo, Mason, and Roscoe 2020), the magic of the situation relies upon the care and attention to detail with which the well-worn myth has been transplanted into an actual setting of the market. Santa’s Lapland as a ticketed venture has emerged from deliberate, strategic action. But it has also been shaped by the interplay of broader technological and material factors: cheap air travel, the non-frozen lake, the digestive habits of reindeer, and so forth. A second point, then, is that any kind of market is constituted by the social and material infrastructures through which it operates.

Although such a view might not seem excessively radical to the management scholars in the room, it represents a very significant break with established traditions in the study of markets. On the one hand there is the economic perspective on markets which tends to see them as passive interfaces between supply and demand. On the other, there is the sociological tradition where markets are the result of social structures, and market actors behave accordingly.

In 1998 the French science and technology scholar Michel Callon published an edited volume called The Laws of the Markets. In the introduction (Callon 1998), he proposed a view of markets influenced by his background as an engineer-sociologist. He suggested that markets comprise sociotechnical assemblages, meaning clusters of people and things, coordinated by expert knowledge. Market actors could be understood as distributed entities, with agency shared out across human individuals and the sociotechnical infrastructures with which they interact. A simple example might be booking flights on a smartphone app – an often frustrating endeavour in which one feels one’s agency decidedly constrained, even as one is empowered to make some sort of sensible decision in the face of the almost infinite possibility of plane tickets.

I arrived in St Andrews in the autumn of 2009 having completed my doctorate and some post-doctoral work. I had not yet found my tribe, as we PhD students were always encouraged to do. Callon had helped me think through my PhD empirics, making some sense of the actions of retail investors as sociotechnical arrangements. There were other people thinking about similar things in a similar way, but not yet a tribe. In 2010 I travelled to Sweden for what was billed as the first interdisciplinary market studies workshop. There, a tribe began to coalesce, and over a regular biannual meeting in Dublin, Provence, St Andrews, Copenhagen, a Covid-delayed remote offering that sadly wasn’t in Grenoble, and most recently Edinburgh, the workshop evolved into a full-fledged multi-track conference. Our former PhD students are teaching a second generation, who airily announce that they are working in ‘market studies’. Market-focused tracks have appeared at the major European conference for the organisation studies community, some of which I have organized. Market studies inflected research regularly appears in journals including Valuation Studies, Finance and Society, Economy and Society, and of course, the JCE. A mammoth 500 page compendium Market Studies: Mapping, Theorising and Impacting Market Action was published by Cambridge University press in 2024 (Geiger et al. 2024).

It is by any measure an established field, committed to detailed empirical investigation of the site in question, sometimes described as an anthropology of markets. My own research has taken in non-professional investing, the genesis of entrepreneurial opportunities – that made a nice Radio 3 essay[ii] – markets for transplant organs, the work of publishers, a detour into the creative industries and intellectual property rights, and another into the moral agencements of financial market practices and the manager as a moral cyborg. There’s a mixture of primary and secondary empirical work here. For our Santa study, observational data were collected by Teea Palo. Teea is now an established scholar but was, at the time, a PhD student paying her bills by working as an elf. This, of course, makes her study an elfnography. The reviewers let that pass, and frankly if it is my sole career contribution to the methodological canon, I will retire happy.

Callon’s third suggestion, perhaps the most radical of all, was that economic theory is constitutive of markets rather than descriptive. That it is, as he put it ‘performative’. In other words, markets are organised in a way that enacts certain theories about rational economic behaviour. Soon afterwards, a series of studies demonstrated how financial economic theory had shaped the construction of futures markets, upholding a narrow interpretation of Callon’s claim; since then a broader interpretation of market theory as policy economics and the professional knowledge of market practitioners, forecasters, traders and so forth has sustained investigations in the field.

It is possible, on the basis of this work, to make certain claims. The first is that any act of market organizing, or design, is also a moment of society organizing. This is because we live in a society where so much is organized around market mechanisms. The second is that people put in a market-type situation will do market type things. This is a point which vexes me less now than it did in my early career. Then it bothered me so much that I wrote a book about it (Roscoe 2014). So let us go back more than a few years to a time where, before smartphones arrived and turned everything upside down with the swipe-left/swipe-right of contemporary relationship formation, the world of technology-driven dating revolved around giant online websites. Our esteemed colleague Professor Chillas and I, then early career researchers, were fascinated by these sites. They were ubiquitous in the media, brandishing big advertising budgets, and our friends were using them. So we set out to establish how they worked. We interviewed dating entrepreneurs, scrutinized patents, read the grey literature, and interacted with the machinery.

The sites worked in different ways (Roscoe and Chillas 2014). Users might fill out a comprehensive questionnaire and leave the business of finding a match to the site’s proprietary algorithms. Or they might be confronted by a set of desired attributes that could be adjusted to configure a desired partner, all the time trading off against scarcity. One site operated a ‘revealed preference’ mechanism, the algorithms watching what users watched and taking this as a more reliable input than their claimed ideal partner. In these various ways, the sites operationalized dating as a process of rational and maximizing selection across a wide array of options.

Such a careful appraisal of others would inevitably lead to the question of what a user’s own ‘stock’ might be worth, so to speak, and what it would ‘buy’ in the market. Indeed, research showed that individuals came to quite a nuanced appreciation of their own value, calibrating their market worth through responses to their profiles, and approaching profiles of equivalent value. In the absence of the social controls that keep real life markets on track, users became strategic in their dealings. They grew younger, taller, and slimmer, presenting idealized versions of themselves and adopting generically appealing likes and dislikes. It seemed that walking on the beach was ever-popular, presumably among readers unfamiliar with the West Sands in February.[iii]

The objection that ‘things have always been thus’ is trivial – the point is that specific market, or market-like, situations perform certain kinds of market behaviour. Instrumentally rational agency is not an innate characteristic, but always already a sociotechnical achievement. Building a dating site invokes certain theories about how participants interact, and if these theories are based on the notion that romance works like a marketplace – even if there’s no money involved – then what is built will look like a marketplace too. On that basis, performativity becomes a ‘moral problem’ (Roscoe 2016).

The dating example also shows how markets are machines for qualifying goods and constituting value. A hot profile, in this context, is the result of algorithmic curation in an attention economy, as well as those not on the West Sands beachside strolls. Through markets we discover new kinds of value, embedded in novel sociotechnical arrangements. In the business school world, an ‘ABS four’ journal paper is a prized thing, yet it has no value outside of the arrangements of listing, ranking, and funding that constitute it. Gem-like as they are, papers are not dug out of the ground as ABS-fours, alas; we make the value of the thing through the market arrangements that we have enacted around it. In fact, there’s plenty of research that shows the same about things that actually are dug up – diamonds, for example, gain their value through the interplay of categorisations and lists that circulate among diamond dealers and assaying laboratories (Mulcahy 2024).

Callon’s final claim is that markets overflow. He took the economic notion of market failure, when things find themselves outwith the confines of the transaction, making them mute ‘externalities’, and rethought it as a powerful mechanism for the change and evolution of markets. Following a productive and highly-cited four-way exchange in this very journal (Butler 2010; Callon 2010; du Gay 2010; Licoppe 2010), a body of work has explored how such overflows, or misfires, give participants and outsiders an opportunity to reshape markets and thereby reorganise society (Gross and Geiger 2024; Mason and Araujo 2021; Cochoy, Giraudeau, and McFall 2010).

My Leverhulme research fellowship, 2016 to 2017, enabled me to chart the formation in the mid-1990s of two smaller company stock markets in London: the London Stock Exchange’s AIM, and the private endeavour OFEX. It is a story of overflows, misfires, and the moves they provoke; of political and regulatory changes, technological advances, shifts in social mores, the career decisions and moves of individuals, and plenty of happenstance. The story seeks to unseat the inevitability of the finance as we encounter it, and instead to sketch out the conditions of possibility that give rise to financial markets in general, and stock exchanges in particular. There’s a lot of detail, and the lesson is one not guaranteed to please those start-up gurus hoping for an easy ‘how to’.

As I wrote in my book (Roscoe 2023), I first encountered these markets in the summer of 1999.

I was a young reporter at the newly formed Shares Magazine. I liked the job. I liked the deal it came with even more: being handed the first gin and tonic as the hour hand crept towards one; riding across London in the back of a black Mercedes, on the way to air my views in a television studio at Bloomberg or the Money Channel; the buzz of young colleagues and new technology and the sense that the world was changing for the better. I liked the fact that a mysterious woman called Bella, whom I never met, used to telephone me regularly for syndicated radio news bulletins that I was never up early enough to hear. Most of all, I liked the smell of money being made and believed that somehow, in a small way, some of it could be mine…

Daniel Defoe wrote of ‘projects’ – start-ups, or entrepreneurial endeavours, we might call them – as ‘vast undertakings, too big to be managed, therefore likely to come to nothing’. He could well have been describing the late 1990s, as the dream of the ‘world wide web’ finally arrived. These were years rich with ‘the humour of invention’, which produced ‘new contrivances, engines, and projects to get money’, as I recalled the outlandish promotions sent roaring into the market by the simple addition of dot-com to the name.

And here is the final thing that needs to be said about markets, a concept that is perhaps more alien to Michel Callon (for a symposium on Callon’s most recent work, Markets in the Making (2021) see Callon et al. (2025); Doyuran, Simiran, and and Unal (2025); McFall (2025). They are performances, both in the sense of social life as scripted but also, more pertinently, in the shape of a spectacle. We can see it in the Santa market, for example, the sense of excess that overflows into the visitors’ tears. Financial markets are often performed in the most outlandish ways, from the men-behaving-terribly antics of the Wolf of Wall Street to the empty, pure spectacle of rocket fantasies or meme coins.

Here we can draw on a whole strand of literature on the interplay of culture and economy, specifically the mutually constitutive relationship between these two ideas, exploring how specific cultural formations become economised and vice versa, as well as the sociotechnical arrangements that support this transformation. The central journal in this space is this one (although other journals are of course available). Here you will find cutting-edge work on financial frontiers, on spectacle, on platforms, on digital trust, on abundance and the history of strolling. Even on the moral economy of market competition in adult webcam modelling, one of our most downloaded papers, I’m afraid to say. There will be lots of very disappointed undergraduates out there.[iv]

You will have noticed that up to now I have been talking about markets under neoliberalism. A slippery term but still a useful one, neoliberalism maps broadly onto the use of the market as a central device for coordinating institutional action and governing society. So, journal rankings, financial trading, tourist trips to Santa. But the times they are a-changing; in fact, it seems they a-changed a while ago. We are now post-neoliberal, say the smart kids in political economy (Davies and Gane 2021; Cooper 2021).

At the heart of the neoliberal project are the assumptions that the market knows best, and that transactions freely entered into are in and of themselves a good thing. A strand of thinking that goes all the way back to Adam Smith emphasises the benefits of commerce: trust, decency, honest dealings, good citizens, turning private vice into public virtue.

The post-neoliberal thinkers look less at Smith and more at Rene Girard, a Stanford-based philosopher who taught tech-barons like Peter Thiel and left a deep and questionable impression (Roscoe 2019). Where Smith infers a distinctly human capability to exchange from two dogs’ inability to do the same, Girard sees the dogs’ competitive envy as the fundamental characteristic of human nature. It’s said that Peter Thiel invested in Facebook because he saw it as a truly Girardian business, its users compelled by primal envy to scrutinised other people’s lives. Post-neoliberalism mixes these ideas with ultra-libertarianism, a dash of paranoia, and a bizarre dose of eschatological excitement. The whole of life should be a gigantic market, with we citizens the mobile goods: a polity comprising city states run like start-ups, with autocratic chief executive monarchs. If you don’t like it, you can simply go elsewhere (Smith and Burrows 2021) No voice, only exit! I presume that Curtis Yarvin, philosopher prince of the new right, doesn’t have kids at primary school.

Post-neoliberalism used to lurk at the margins, sniping at the centres of power. But not anymore. It’s all looking very worrying. The problem I’d like to raise is this: what should we, as scholars of markets say about this new world? How should we approach markets after neoliberalism? Do our tools still work when capital dreams of Mars and memecoins? For spectacular markets, scam markets, excessive markets, paranoid markets, even: markets constituted entirely by ‘vibe’ not virtue? (Muniesa 2024; Swartz 2022) Are our implements still fit for purpose?[v]

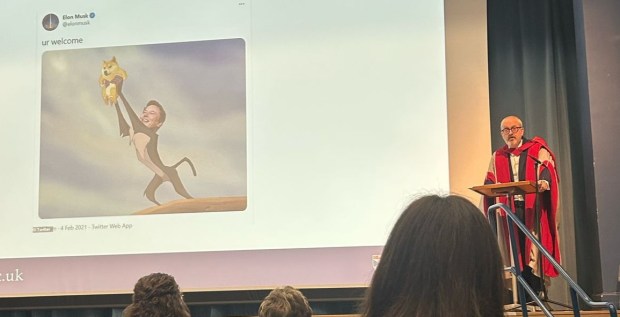

I think they are. Take Mr Musk. Not Musk the man, so much as Musk the ‘collective delusion’ (Kriss 2024): the spectacle, hurling insults and refusing to stand by them, preening on Saturday Night live; the rocketeer and Mars colonist carried on a wave of sheer make-believe money, dogecoin to the moon; the fact that he is a kind of ontological hybrid of capital and fantasy and carnival, a figure who is more meme and reddit chat than analyst briefing and dividend. Like Bruno Latour’s Pasteur (Latour 1988), he is more than a man: an assemblage, a network, a mixing pot of culture, technology, performance and financialization. Such a figure proves immune to critique unless we take the time to disassemble the network, the performance, the points of passage through which the thing colloquially known as Daddy Elon comes into being. In doing so we might strip away the genius mythmaking and eventually reveal something really quite ordinary (Kriss 2024): trivial in every sense apart from its consequences.

An approach to markets that recognizes the interplay of culture and economy in the construction of value can help us to make sense of the citational performance of spectacle, sensation and affect that brings a memecoin to life as an economic artefact. Perhaps it will even help us disentangle the fact that the Department of Government Efficiency is a joke on a currency that itself is spectacle and second order joke. Or perhaps that, too, is just a scam.

You might ask what this means to us as scholars in the business school – that paradigmatically neoliberal institution. The UK’s business schools inherited a left-of-centre perspective from industrial sociology and longer standing studies of work and organization. The same is not the case elsewhere. Peter Thiel used to give a lecture in his startup course at Stanford titled ‘Founder as Victim, Founder as God’ (Ibled 2025) with ruminations like ‘should Richard Branson be king?’, many strange bell graphs about traits, and images of sacrifice. Rene Girard, pop philosophy, and faux science on the curriculum at one of the world’s most influential business schools – we should all beware. We know this, by the way, from the published class notes of student Blake Masters, who subsequently co-wrote Thiel’s book, became a successful venture capitalist and an unsuccessful congressional candidate.[vi]

For the title of my lecture I took the liberty of citing St Andrew’s University’s most distinguished honorary graduate, the strangle-toned folk-legend Bob Dylan. Apologies to Dylan fans, on all counts. When he wrote in the first verse that the waters around us have grown, and we better start swimming or sink like a stone, I think he was trading in metaphor. Standing here on our tiny promontory at the edge of the wild North Sea, it seems to me that we are all out of allegory. The times have changed, the waters really are rising, and we need to figure out what to do about it.

My sense is that we can only meet performance with performance.[vii] A performance through research, of course, producing (as I have written elsewhere) ‘a kind of rich, descriptive realism that encapsulates a politics all of its own’, but also a pageant of snark, meme, slippery ironic insincerity, already the enemy’s weapons of choice; a ‘humourful engagement’ with markets that, in the words of Isabelle Stengers, may ‘lighten the object of critique’ and complicate the life of power (I am here following de Goede 2020, 109). The carnival, de Goede argues, can transform people’s everyday experiences of finance, challenging its rationality and exposing its contingency (De Goede 2005). My book, for example, wields a kind of self-destructive ‘gonzo’ where a young, naïve, plump version of me becomes an unwitting accomplice to various kinds of financial skulduggery. It aims to create space, to create a dissonance and uncertainty, to leave the sense that finance is not as clever as it thinks it is. The book works: people read it and laugh, and in the end that’s enough.

Come writers and critics, the chance won’t come again, Dylan wrote. We can mount our own interventions in our writing and our teaching: guerrilla writing, gonzo teaching, writing for readers, teaching for students, doing both with humour, and even – perhaps – with style. We can fill the curriculum with ‘bad economics’, in Joyce Goggin’s (2013) phrase, a deliberate re-entangling of personality and particularity with markets. This is how our practice should confront the strange, destructive markets that come after neoliberalism. This is how we should study them. And as for the pantomime villains who parade within them, these people need nothing from us apart from earnestness.[viii] That much we can withhold.

Thank you very much.

And the references

Butler, Judith. 2010. “Performative Agency.” Journal of Cultural Economy 3 (2):147-161. https://doi.org/10.1080/17530350.2010.494117.

Callon, Michel. 1998. “The embeddedness of economic markets in economics.” In The Laws of the Markets, edited by Michel Callon, 1-58. Oxford: Oxford University Press.

———. 2010. “Performativity, misfires and politics.” Journal of Cultural Economy 3 (2):163-169. https://doi.org/10.1080/17530350.2010.494119.

———. 2021. Markets in the making: Rethinking competition, goods, and innovation. Princeton: Princeton University Press.

Callon, Michel, Langley Paul, Maurer Bill, Mitchell Timothy, Roth Alvin, and Koray and Caliskan. 2025. “Review Symposium: Michel Callon’s Markets in the Making: Rethinking Competition, Goods, and Innovation. Zone Books.” Journal of Cultural Economy 18 (1):154-167. https://doi.org/10.1080/17530350.2024.2413105.

Cochoy, Franck, Martin Giraudeau, and Liz McFall. 2010. “Performativity, Economics and Politics.” Journal of Cultural Economy 3 (2):139-146. https://doi.org/10.1080/17530350.2010.494116.

Cooper, Melinda. 2021. “The Alt-Right: Neoliberalism, Libertarianism and the Fascist Temptation.” Theory, Culture & Society 38 (6):29-50. https://doi.org/10.1177/0263276421999446.

Davies, William, and Nicholas Gane. 2021. “Post-Neoliberalism? An Introduction.” Theory, Culture & Society 38 (6):3-28. https://doi.org/10.1177/02632764211036722.

De Goede, Marieke. 2005. “Carnival of money: Politics of dissent in an era of globalizing finance.” In The Global Resistance Reader, edited by Louise Amoore. London: Routledge.

———. 2020. “Engagement all the way down.” Critical Studies on Security 8 (2):101-115. https://doi.org/10.1080/21624887.2020.1792158.

Doyuran, Elif Buse, Lalvani Simiran, and Sevde Nur and Unal. 2025. “Reading Callon at Zuccotti Park.” Journal of Cultural Economy 18 (1):168-174. https://doi.org/10.1080/17530350.2024.2443981.

du Gay, Paul. 2010. “Performatives: Butler, Callon and the moment of theory.” Journal of Cultural Economy 3 (2):171-179. https://doi.org/10.1080/17530350.2010.494120.

Geiger, Susi, Katy Mason, Neil Pollock, Philip Roscoe, Annmarie Ryan, Stefan Schwarzkopf, and Pascale Trompette. 2024. “Market Studies: An Interdisciplinary Approach to Mapping, Theorizing and Impacting Market Action.” In. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

Goggin, Joyce. 2013. “Bad economics: hard cash/soft culture.” Tamara: Journal for Critical Organization Inquiry 11 (2).

Gross, Nicole, and Susi Geiger. 2024. “Tinkering in Markets for Collective Goods: Experiments, Exceptionalities and the Case of HIV Medications.” In Market Studies: Mapping, Theorizing and Impacting Market Action, edited by Susi Geiger, Katy Mason, Neil Pollock, Philip Roscoe, Annmarie Ryan, Stefan Schwarzkopf and Pascale Trompette, 23-37. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

Ibled, Paula. 2025. “‘Founder as Victim, Founder as God’: Peter Thiel, Elon Musk and the two bodies of the entrepreneur ” Journal of Cultural Economy.

Kriss, Sam. 2024. “Very ordinary men: Elon Musk and the court biographer.” In The Point Magazine.

Latour, Bruno. 1988. The Pasteurization of France. Translated by AM Sheridan and J Law. Cambridge, Massachusetts: Harvard University Press.

Licoppe, Christian. 2010. “The ‘Performative Turn’ in Science and Technology Studies.” Journal of Cultural Economy 3 (2):181-188. https://doi.org/10.1080/17530350.2010.494122.

Mason, Katy, and Luis Araujo. 2021. “Implementing Marketization in Public Healthcare Systems: Performing Reform in the English National Health Service.” British Journal of Management 32 (2):473-493. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1111/1467-8551.12417.

McFall, Liz. 2025. “My attachment to Michel Callon’s markets.” Journal of Cultural Economy 18 (1):147-153. https://doi.org/10.1080/17530350.2024.2349594.

Mulcahy, Rian. 2024. “Facets of Worth: Valuation Processes in the Polished Diamond Market.” In Market Studies: Mapping, Theorizing and Impacting Market Action, edited by Susi Geiger, Katy Mason, Neil Pollock, Philip Roscoe, Annmarie Ryan, Stefan Schwarzkopf and Pascale Trompette, 165-175. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

Muniesa, Fabian. 2024. Paranoid Finance. Cambridge: Polity.

Palo, Teea, Katy Mason, and Philip Roscoe. 2020. “Performing a Myth to Make a Market: The construction of the ‘magical world’ of Santa.” Organization Studies 41 (1):53-75. https://doi.org/10.1177/0170840618789192.

Roscoe, Philip. 2014. I Spend Therefore I Am. London: Viking.

———. 2016. “Performativity as a moral problem.” In Enacting the Dismal Science: New Perspectives on the Performativity of Economics, edited by Ivan Boldyrev and Ekaterina Svetlova, 131-150. Palgrave MacMillan.

———. 2019. “Strategy, Spectacle, or Self-emptying? Sacrifice and the Search for Business Ethics.” In Mimesis and Sacrifice: Applying Girard’s Mimetic Theory Across the Disciplines, edited by Marcia Pally, 190-202. London: Bloomsbury.

———. 2023. How to Build a Stock Exchange: The Past, Present, and Future of Finance. . Bristol: Bristol University Press.

Roscoe, Philip, and Shiona Chillas. 2014. “The state of affairs: critical performativity and the online dating industry.” Organization 21 (6):797-820. https://doi.org/10.1177/1350508413485497.

Smith, Harrison, and Roger Burrows. 2021. “Software, Sovereignty and the Post-Neoliberal Politics of Exit.” Theory, Culture & Society 38 (6):143-166. https://doi.org/10.1177/0263276421999439.

Swartz, Lana. 2022. “Theorizing the 2017 blockchain ICO bubble as a network scam.” New Media & Society 24 (7):1695-1713. https://doi.org/10.1177/14614448221099224.

[i] My thanks to Teea Palo for allowing me to use this empirical material for this lecture and its publication. I draw here on our joint project, (Palo, Mason, and Roscoe 2020)

[ii] https://www.bbc.co.uk/programmes/b0195q98

[iii] The iconic beach at St Andrews, film location for Chariots of Fire’s famous scene. On a February day, the North Sea’s Baltic winds can blow in hard.

[iv] Our esteemed colleague, JCE associate editor Jose Ossandon deserves credit for this wisecrack.

[v] Fabien Muniesa has arrived at the same conclusion, via an analysis of paranoia and the semiotics of finance. His concludes ‘paranoia puts oneself in the position of guarantor of truth. Making fun of that – of truth and its guardians – is a dangerous business. It creates a space for equivoque and drift… perhaps, also as a condition for critique: a critique that may succeed where paranoia has failed.’ (Muniesa 2024, 60) p60.

[vi] See https://blakemasters.tumblr.com/post/24578683805/peter-thiels-cs183-startup-class-18-notes [accessed 17 March 2025]

[vii] A commitment shared by this journal in publishing, supporting and commissioning diverse textual and non-textual content, from the architectural photographer Simon Phipp’s ziggurat drawings featured on our cover (see https://www.simonphipps.co.uk/information/) to the urban film essays and installations made by Sapphire Goss, Liz McFall and Darren Umney https://www.youtube.com/@areweawed8955

[viii] It’s telling, but also ridiculous, that the only attack Musk has really responded to in recent months is the claim that he cheats at video games. See https://www.washingtonpost.com/technology/2025/01/29/elon-musk-video-games-diablo-path-exile/