In Sptember 2025 I was delighted to be invited to spend two days with the Science and Technology Studies group at DTU Management. Great conversations, great hosts, and a hired green bicycle to enjoy Copenhagen in the autumn sunshine (it’s a long ride to Lyngby, but so much nicer to be on the bike than the metro). Meetings, a publishing workshop for the ECRs, and a talk on the ‘Apocalyptic futures of the economy’, a topic that I’ve been working on for a while. I’m trying to figure out what all the craziness and second-rate sci-fi references mean for markets (and for those who study them). Something, I’m sure.

Here it is -Enjoy!

I went to see the Matrix in the cinema in 1999, aged 25, and thought it was, well, ok. It was silly and fun, as was the media fuss about the cast being made to read Baudrillard. How could I have possibly known that it would become such a canonical and toxic point of cultural reference that almost 30 years on I would be putting it on a slide to talk about bogus economics. But here we are: in the midst of a cluster of ideas about economic organization that can only be made sense of through bunkum thought articulated in terms of cod-philosophy, sci-fi images, HP Lovecraft and Harry Potter, where you have to rewatch LoTR to make sense of the naming of names. I am always already too old for this nonsense.

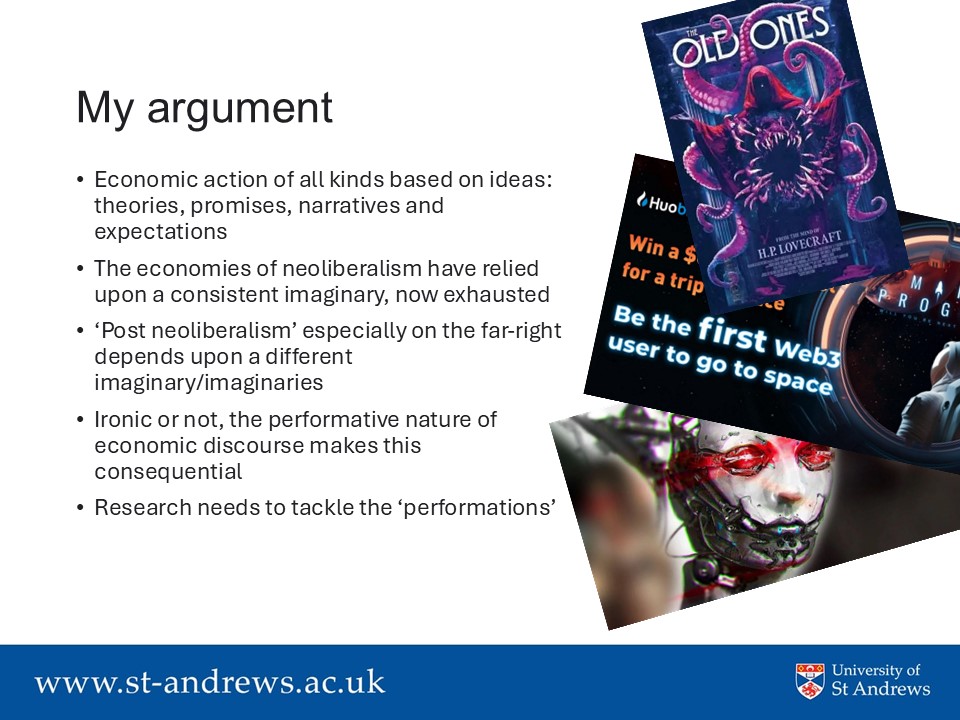

Economic activity gains much of its legitimacy from promises, narratives and expectations. The ‘performativity programme’, most broadly understood, tracks the flow of ideas through the institutional capillaries of discourse, metrology, technological networks, and the rest. But, surveying the ruins of neoliberalism, Jens Beckert concludes that its promises have been exhausted. This paper seeks to make sense of what might come next: extending the performativity programme to markets that are no longer doux – if indeed they ever were – but organized around envy, fear and loathing. Less polemically, it sets out to synthesise a heterogeneous cluster of imaginaries championing expansive but also restricted visions of liberty, political narrowness, religious conservatism, nationalism and overt racism. Yet these are market imaginings, irretrievably connected with processes of production, investment, expansion and speculation; even preparing for the end of the world is an exercise in individual consumption.

I read these ideas as techno-capitalist intellectual formations that are meaningful only under the conditions of their specific sociotechnical arrangements. These imaginaries circulate in a literal market for ideas, defined by the technical affordances of the digital world, and rewarded by the capital and social connections attached to that same world. My synthesis is organized around the eschaton: a motif common to this cluster of thought, though presented in various ways. I propose a cyclical account of these ideas divided into three stages: the fear of death; a messianic redemption; and futures of freedom and purity. Having presented this account, I employ a performativity-style analysis to explore how these ideas are enacted, or at least prefigured, in economic arrangements. Finally, I consider what the performativity programme might not see, topics for future research as scholars grapple with the changing stories of economic organization.

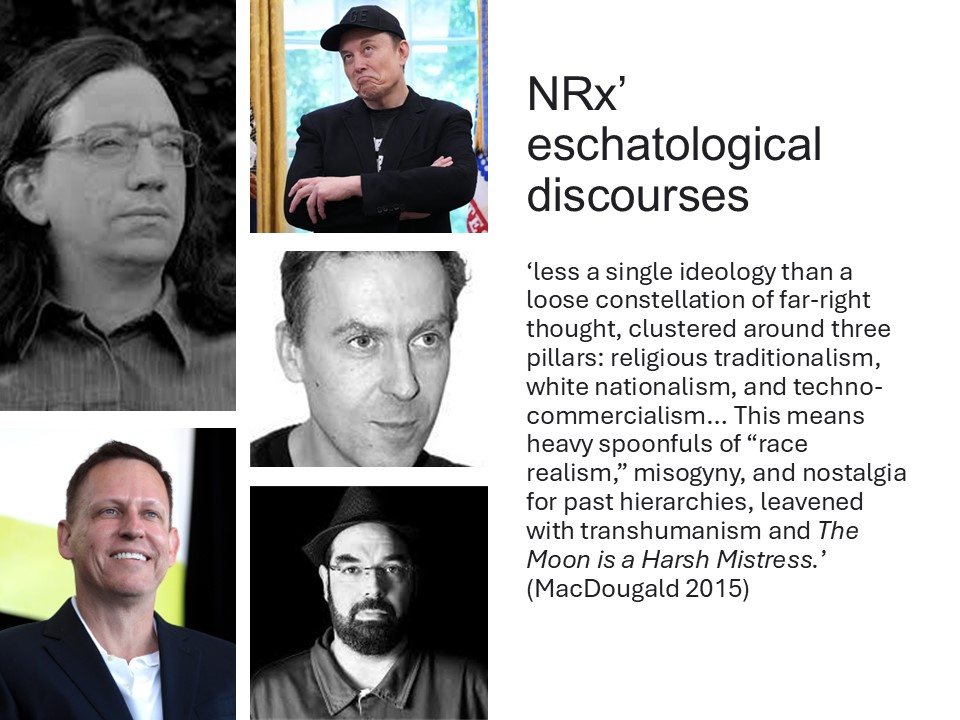

The discourses of the post-neoliberal economy are fragmented. Even zooming in on one particular context, the NRx or the ‘New Reactionaries’ of Silicon Valley’ there remains considerable variety. Nonetheless, it is possible to identify some common areas of concern – fixations, and I’ve tried to sort them out into the eschatological cycle they reveal. I am not the first to note these connections: the eschatology of Silicon Valley, with its ‘end of uncertainty’, is long established. Even in the mainstream of financial thinking there is, writes Muniesa (p. 46),

‘an obsession with the notion of the future, seen as something exhilarating and revolutionary, but also apocalyptic (this is always about a sort of an endgame), wrapped in the jargon of vision, disruption and also liberation – liberation of the body, or from the body, or of the soul, or from the soul, liberation of everything from everything else, in a kind of a transhumanist fashion.’

And yes, it’s men, always. Horrible, nasty men. Elizabeth Sandifer (2017) identifies three thinkers as being central to what she calls the ‘genre of sprawlingly mad manifesto-like magnum opuses’ that characterize the thinking of the new right. These are Eliezer Yudkowsky, Curtis Yarvin, and Nick Land, names long familiar to researchers of the new right but more recently regular fixtures in long read ‘how we got here’ pieces in the mainstream media. I also consider the tech barons Elon Musk and Peter Thiel, and the thinking of Rene Girard. I haven’t steeled myself to read The Sovereign Individual yet, but when I do there will be a Ress-Mogg in here as well. What a cast! It’s all going to be good.

Death, or at least the extraordinary fear of it and fixation with it, underpins the rest. In the thought of the new right, it takes specific forms. There is an obsession with disease and decay, made clear in Thiel’s determination to rid the world of sickness and weakness, via such means as parabiosis (the transfusion of younger people’s blood), cryogenics (freezing), and transhumanism (a merging with computer code). It is often difficult to distinguish between genuine aspiration and science-fiction coded fantasy here. Silicon Valley booster Ray Kurtzweil, principal researcher and AI visionary at Google (a job definitely in the ‘nice work if you can get it’ category) speaks of ‘longevity escape velocity where every year of life we lose through ageing we get back from scientific progress’, a moment expected in the 2030s. Elon Musk’s theatrical claims about colonizing space are set against the concern that humanity’s time on earth is threatened by vague catastrophe, ecological or otherwise. Malthusian ideas about population growth are a common trope, as are the fears that society faces a vague, unspecified breakdown, or ‘the end of the world as we know it’. The causes of existential crisis are ill-defined: Lovecraftian fears of the outside, pandemic, social collapse, or zombies. Precision here matters less than vibe.

Perhaps the most notable – and specific – eschatological trope is the AI singularity. The thinking goes as follows: As AI improves through feedback loops, often in ways that confound its engineers, the pace, magnitude and independence of the AI will increase exponentially. Eventually it achieves a god-like omnipotence, its datasets equating to the entire world and everything in it. This is a technologist’s apocalypse.

Nick Land has made a conceptual link between capitalism, as a self-propelling, ever accelerating, inhuman phenomenon, and AI, building on a long history of thinking of the market economy in cybernetic terms. Land, whose eccentric intellectual career has been widely chronicled, combines misanthropic pessimism with a cyberpunk aesthetic and a reverence for the authoritarian capitalist regimes of Shanghai (where he lives) and Singapore. Commentators are struck by the inhumanity of his thinking. Land espouses a supposedly Deleuzian ‘accelerationist’ position where the institutions of liberal society are merely a speedbump on the road to humankind’s destiny and need to be swept aside. Capitalism eventually consumes us all: the ‘inevitable death flow’, he wrote.

No matter. With its infinite computational resource the AI will be able to digitally recreate the living (or even the dead) in its digital ‘spaces’. These kind of ideas are the meat and drink of professional boosters like Kurzweil, who proposes to bring his father back to life on the basis of a collection of artefacts and is cramming himself with a cocktail of vitamins and medicines to prolong his own life so that he might see, and benefit from, the coming singularity.

Knowledge of a forthcoming omniscient AI presents its holders with a problem: will the AI-god be nice or nasty? Probably nasty, say those who take the time to speculate on this matter (Kurzweil does not). Yudkowsky, a computer scientist, blogger and manifesto writer, is the founder of the Machine Intelligence Research Institute, a think tank devoted to mitigating the risk posed by the arrival of a superintelligent artificial intelligence. Yudkowsky is also the founder of an online community called ‘lesswrong’, devoted to the cause of reinventing human behaviour from the first principles of probability theory.

For this community, it is axiomatic that the future AI will be capable of bringing us all back to life in his digital circuit boards, where will live like avatars in a science-fiction futurity. It is in this context that a user named Roko pointed out that such an intelligence, able to read through its infinite archives and establish who assisted and who did not, would decide to retrospectively encourage participation through the application of eternal torment on the future digital selves of those who chose not to. This probability-scripted futurists’ version of Pascal’s Wager hit hard. It clearly upset Yudkowsky, who replied:

Listen to me very closely, you idiot. YOU DO NOT THINK IN SUFFICIENT DETAIL ABOUT SUPERINTELLIGENCES CONSIDERING WHETHER OR NOT TO BLACKMAIL YOU… I’m banning this post so that it doesn’t (a) give people horrible nightmares and (b) give distant superintelligences a motive to follow through on blackmail against people dumb enough to think about them in sufficient detail, though, thankfully, I doubt anyone dumb enough to do this knows the sufficient detail.

To explain this, I can only defer to Haider, who writes: ‘by telling us about the idea, Roko implicated us in the Basilisk’s ultimatum. Now that we know the superintelligence is giving us the choice between slave labor and eternal torment, we are forced to choose. We are condemned by our awareness. Roko fucked us over forever.’

There are many ways to approach this. It is an intellectual world, an urban myth and a cultural artefact. It has its own Wikipedia page, which tells us that no one took it very seriously, and that the popstar Grimes made a joke about it in a song, which led directly to her marrying Elon Musk. It’s plainly nonsense, which makes me safe from eternal torment, for Roko admits in his post ‘that the probability of a CEV doing this to a random person who would casually brush off talk of existential risks as “nonsense” is essentially zero.’ (As exhibit B for the category of nonsense, the same post contains the sentence ‘I swear that man [Elon Musk] will single-handedly colonize Mars, as well as bringing cheap, reliable electric vehicles to the consumer’.)

It’s a story about technology, markets, and capital that makes sense in a wider nexus of market imaginings. Like all fictions it is simultaneously believed and not believed; it can be the stuff of nightmares and disclaimed the next moment. It demonstrates the entanglement of futurity, technology, and the market. The basilisk is self-fulfilling, in as much as it directs capital flows to AI research, and importantly to Yudkowsky’s safe-AI institute. It also performatively forecloses certain other futures, for example, one where the AI singularity never happens and diminishing rates of return throttle technological advances, and all the nice salaries that go with them.

In such readings of the eschaton, technology, capital and the market are inseparable; for the philosopher Land this is precisely the nature of capital. For Peter Thiel, man is fallen, destroyed by technology and ‘the shimmering promise of godhood’

What is needed is a messiah. Fortunately, we have one, especially as expressed in the discourses of men like Musk and Thiel. The founder-entrepreneur is a messianic figure, a thaumaturge, a founder of new dynasties and lineages. As with the figures discussed above, there is an intellectual genealogy of note. It has, in recent months, come to wide attention that Thiel and his disciples were themselves acolytes of the Stanford philosopher Rene Girard. Displaying a contempt for disciplinary boundaries that perhaps appealed to these nascent disruptors, Girard excavated a syncretic theory of human society as based on imitation. For Girard desire is a learned, social phenomenon that originates in an already existing desire. The more mimetic desire is, the more intense it becomes. Dressed in the garb of a revelation drawn from the greats of western literature, such commonsense wisdom sits comfortably with the tech bros, the rhetorical space between a pretend universality and a far more modest claim that is so self-evident as to be a cliché (writes Adrian Daub) Girard provided for Thiel a ‘mystical knowledge that was, when stripped of its rarefied vocabulary and references, really not [PR1] that different from the common sense of his particular milieu’.

Where Girard’s revelation promised salvation through self-knowledge, Thiel’s reading singles out the elite, the insiders, the chosen few – the founders. For Girard, mimetic violence can only be ended by the sacrifice of a scapegoat; he finds the ultimate scapegoating in the passion. Carla Ibled, in her excellent recent paper, notes that Musk and Theil present themselves as risk takers, those who undergo sacrifice, and who suffer. Musk brags of the long hours he works (and imposes on workers) and his ability to take ‘insane risk’. In 2012 Peter Thiel taught a class in Stanford, titled ‘Founder as Victim, Founder as God’, recorded in the class notes of Blake Masters, who subsequently became Theil’s co-author, a venture capitalist, and has twice run for Congress supported by Thiel. Wikipedia describes Masters as ‘venture capitalist, author, former political candidate, and conspiracy theorist’. In these, perhaps less guarded, pronouncements Thiel uses the same vocabulary of power, exception and importance to describe the founder as he does the sacrificial scapegoat.

In Zero to One, the book that grew out of these lectures, Theil actually says something very strange: ‘Oedipus is the paradigmatic insider/outsider: he was abandoned as an infant and ended up in a foreign land, but he was a brilliant king and smart enough to solve the riddle of the Sphinx.’ This is a bizarre misreading of the dramatic tension of the play, where for all Oedipus’ intellectual ability he is unable to see clearly his own future, and his own catastrophic failure; it’s as if Theil casts himself as Oedipus, without appreciating the inner blindness that leads to his crime and is dramatized as he gouges his own eyes.

(Oddly, Masters’ class notes refer to ‘the incest accusations’, as if Oedipus’ estate might retain a Silicon Valley lawyer, just in case.)

‘Normal people aren’t like Oedipus or Romulus’, he claims, and by analogy, neither are founders. He presents ‘the founder as a kind of primal father’ (writes Melinda Cooper), an antinomian figure who destroys old laws and creates new ones, who looks to the far-off technological future while seeking to resurrect the most arcane social hierarchies.’ In From Zero to One the section on Steve jobs is titled ‘the return of the King, and here, as in so many other places, one is unsettled by the constant linking of ancient myth, popular culture, futurism and technology.

The role of the messianic founder/scapegoat/hero/king is to lead his people to a promised land, a terra nova of purity, be that a geographic enclave, a purity of race, a new frontier of technology, new settlements on the sea, or even outer space. Doing so requires an exit. Yarvin, evangelized by Land, calls for the collapse of the nation state into autonomous neo-cameralist city states; this is also the theme of the Sovereign Individual, a hard-right late-90s techno-futurist self-help book published at the dawn of the digital age, and another of Thiel’s declared great inspirations. But it’s also the world of Neal Stevenson’s Snow Crash (also the book that invented the metaverse) and I can’t help thinking that this text has contributed more to the genre than 18th century German mercantilism.

To where does one exit? To somewhere better, free from the corruption of the ordinary world and the failings of politics: to the digital paradise of eternal life in a machine, for example. Code provides unlimited opportunities for the discovery of new lands. Yarvin, in his day job as software engineer, founded Tlön Corporation as a vehicle to reinvent the internet from ground up in a new space. This is called Urbit (named, like Tlön, after a Borges fable). Another example is provided by the Seasteading Institute, an attempt to produce an engineering blueprint for floating communities on the sea that could function as self-governing, mobile communities. The founder of the institute is Patri Friedman, grandson of Milton and son of David, inheritor of the family’s libertarian ideas and social capital.

Land offers the neologism ‘hyperstition’, whereby fictional ideas shape expectations, efforts and designs, and crucially the flow of investment capital. Land’s 1990s Warwick-based research institute was transfixed by William Gibson’s Neuromancer the influence of science fiction is ongoing; hyperstition can ‘can be defined as the experimental (techno)-science of self-fulfilling prophecies’. In this view, Seasteading and Urbit exist as socio-technical mechanisms of prefiguration and experimentation. Whether they succeed, which remains highly unlikely, matters less than what they can show about the possibilities of the future, and how in doing so they might influence ongoing economic and political formations. It is unlikely to be coincidence that one notable founder of Yudkowsky’s think tank, Urbit and the Seasteading Institute is Peter Thiel, who has also invested heavily in surveillance software, as well as backing a cohort of hard-right young white men, notably JD Vance, on the road to power.

The STS-inflected literature on markets has long made a similar point: technological expectations shape capital flows and organizational choices, and thus become performative. The do so through being incorporated in the socio-technical assemblages of markets and organizations. It is said that Theil invested in Facebook – from which he made his second vast fortune – because he recognized it as a Girardian business; it can equally persuasively be argued that Theil’s investment was a mechanism through which Girardian ideas about social imitation as the driving force in markets became operationalised in social media.

Other manifestations of these promissory expectations, and the concrete realization of life after the exits made possible by capital, come in the form of what Atkinson and O’Farrell dub ‘libertectures’: their catalogue includes private cities (such as the ill-fated Neom, where costs have reportedly bloated to the multiple-trillions); gated communities and other micro-jurisdictions; private airports; freeports; libertarian digital spaces, of which Yarvin’s Urbit might be an example, or Yudkowsky’s digital Valhalla; pioneer enclaves (such as Seasteading and Mars); and ‘necrotectural space’, empty residential units held for speculative investment. Or the patrimonial capitalism mapped by Cooper, a new set of game ‘rules’ operationalized through novel share structures that have securing dynastic fortunes for generations – again, Peter Theil and his founders fund are central players.

This brings us back to the genre of syncretic apocalypticism that I have been attempting to systematise. We can usefully call it ‘internet thought’, and it is organised around a specific set of sociotechnical assemblages – the world of social media and online publishing, free from the constraints of traditional academic or literary structures and understandings of quality.

To take a pertinent example, Yarvin’s prose is universally derided for its verbosity, eccentricity, and inane thought experiments, which paired with short, declarative sentences and three sentence paragraphs makes extended engagement hard work (from his influential ‘A brief explanation of the cathedral’:

‘So the difference between our government, and a government which is “power-tight,” is as basal as it could be—not like the difference between a goat and a gazelle, like the difference between a gazelle and a chanterelle. There isn’t really, like, a kind of surgery that will turn either of these things into the other.’ (Italics in the original.)

But Yarvin’s prose is extremely effective within the sociotechnical assemblage outlined above, the world of newsletter publishing where technological affordances suggest skimming, reposting, and the rapid sharing of morsels of content, all in pursuit of the next moment of ‘pwnage’.

Internet thought is structured by spectacle, shitposting and charismatic authority. ‘Online one can inhabit ideological conflict anywhere and all the time,’ writes Finlayson. ‘Its very ubiquity is evidence of a political-economic ontology which demands that one participate in that online conflict, intensify it and win it. Success as an ideological entrepreneur is its own reward and its own proof’. Concepts are dislocated, hyperlinked and recombined: ‘this style of intellectual life is a natural outgrowth of the Internet, with its rabbit holes, endless threads, and broken links.’

The ‘Red Pill’, the symbolic moment of liberation, is itself a socio-technical assemblage. It always was: in the movie, the pill itself was only a sign, ‘part of a trace program, designed to disrupt your input-output signal so we can pinpoint your location,’ as Morpheus explained. The red pill of the new right is taken by swallowing the discourses of message boards, online communities, conspiracy theories: the term entered popular usage after Yarvin’s invocation of his own red pill, ‘the size of a golf ball… a sodium metal core…’.

These spaces, while actually existing, are also prefigurative. Neom, in reality a mess of barely started projects and cost overruns, exists in rich digital renderings and discursive accounts. It is a hypertstition, an attempt at future making. The future in question is one of radical separatism, with a patrimonial ruling class waited on by a geographically and racially differentiated underclass. This is the stuff of fascism, and it is on display in all of the above examples. But these ideas – of the end, of redemption, and of eventual pure life somewhere else (in the compound, the computer, the hyper-racial accelerated cyborg city) must be read as simultaneously true and not true, an example of the generalized and networked ‘scamful relations’ that Swartz (2022) highlights as the precondition for contemporary economic action. After all, what is the point in establishing a dynasty if one really believed that the world was going to end?

My provocation, then, is that what seem like crazy ideas are windows onto a different way of understanding market relations, and that these imaginings are performative. Vast sums of capital are being deployed in experiments with new social formations, just to see. For Girard, Land, and other thinkers of the new right, markets are not engines of freedom. They are built on foundations that do not fully understand the laws of society or technological progress. The markets we might encounter now are not those envisaged in the Smithian tradition. They draw on charismatic authority, fictionality, expropriation, eschatological fantasy and surveillance technology. These hyperstitions can be seen as guerilla interventions, that make sense only when the liberating army is just over the horizon. The eschaton, the end of the world as we know it refers not to biosphere but to the social organization we have inherited from the 19th century: the nation state, the institutions of liberal democracy, whig ideas of progress as a general public good.