I dissect Silicon Valley Bank’s utopian problem in a recent piece for the Transforming Society blog…

Tag Archives: economics

BBC Radio 3 Freethinking on Debt

Twas the night before Budget day and all through the house, nothing was stirring but BBC Radio 3 Freethinking and a very excellent discussion on ‘Debt, from the South Sea Bubble to Sunak’. As the nation waited for Chancellor Jeremy Hunt’s next moves on the UK’s crisis ravaged economy, Anne McElvoy hosted a high powered panel: Professor Kenneth Rogoff, Maurits C. Boas Chair of International Economics at Harvard University; Vicky Pryce, former Joint Head of the United Kingdom’s Government Economic Service, Dr Dafydd Mills Daniel, lecturer in Divinity from the University of St Andrews, and of course, your humble correspondent. It was a fun discussion – I hope you enjoy listening!

The ‘Anthropology of Entrepreneurship’ by Richard Pfeilstetter

On 2 November, I was given the opportunity to participate in a panel debate – a ‘book lunch’ (very droll!) – for anthropologist Richard Pfeilstetter’s recent (2022) book ‘The Anthropology of Entrepreneurship.’ Thank you Richard for the invitation and to Kirsty Osborne and the University of St Andrews Entrepreneurship Centre for organizing. I ended up writing a review of sorts. Richard felt it was worth sharing, so here it is (in a slightly tidier form).

“Thank you everyone for the opportunity to participate in this discussion, to Kirsty for organizing. I found Richard’s book simultaneously engaging, challenging, stimulating and at times infuriating. For an outsider to anthropology the book provided an engaging and swift tour of the strange history of entrepreneurship studies in anthropology. The source of my infuriation was simply that the tour is, for an outsider, sometimes a little too swift. Richard has managed to cram so much into a slim volume. So much, but at times, and necessarily, never quite enough.

Richard’s argument centres on a call for anthropology to take entrepreneurship seriously. He is bothered that anthropological scholarship often dismisses anthropology as a native term, something that doesn’t need to be explored reflexively, but just can be deployed in situ. Hence, he suggests, the willingness of much contemporary anthropology to regard entrepreneurship as part of a programme of social coercion and behavioural adjustment on the part of neoliberal elites.

At the same time, Richard is cautious of the move to regard any kind of social-change maker as an entrepreneur, pushing instead for some kind of basic rigour in the definition. In his book we meet all kinds of entrepreneurs, many of them sole traders or disenfranchised individuals, but there is always a commonality of economic activity.

It reminds me of the definition in the first non-humanities academic book I ever read as I started to drift towards the world of management research: Peter Drucker’s Innovation and Entrepreneurship, published in 1985. Drucker offers a definition of an entrepreneur as someone who transfers resources from a lower value to a higher value part of the economy. In some ways this is a tendentious definition, very 1985, because it posits that the true entrepreneur is defined by success. Druker goes on to suggest entrepreneurship is low risk – tell that to the struggling and marginalized entrepreneurs in Richard’s compendium! But, in other ways, as Richard demonstrates, requiring an attempt to generate value from enhancing economic returns as a very minimum for the definition does give us a common object of conversation, preventing the concept from becoming meaninglessly diluted.

Richard’s approach also captures something of the original sense of entrepreneurship, from entreprendre – the go between – in the work of Jean Baptiste Say. A focus on the often mundane efforts of economic toil compares favourably with the offering of Daniel Defoe, who a century before Say, wrote of ‘projects and projectors’, undertakings so fanciful and bold that they are almost certainly doomed to fail. If the kingpins of Silicon Valley are Defoe’s ‘projectors’, speculative dreamers of a new economic reality, so Richard’s entrepreneur is the diligent intermediary in the production process. How refreshing to regain that focus, especially amongst the recession, inflation, and general political-economic turmoil that the UK now faces.

Back to anthropology. It strikes me – and Richard is perfectly aware of this – that anthropology is somewhat late to the party. There is a huge and flourishing literature of entrepreneurship, much of it functionalist and, dare I say, rather dull, but some of it critical and ethnographic in nature. At the same time the anthropological method – observation, thick description, an awareness of history, culture and context has spread wide. My own field, following thinkers like the late Bruno Latour, has for two decades espoused an anthropology of markets. Moreover, it is genuinely interested in its objects of investigation, whereas, in Richard’s account, anthropology’s own attempts to get to grips with entrepreneurship have been driven by the discipline’s intellectual history. The method has even made its way to the airport bookshelves: see Gillian Tett’s ‘Anthrovision’, a defence of the ethnographic virtues of looking, listening and understanding in the age of top-down, big-data-driven social science, policy and planning.

It just so happens that the University’s new strategy was published yesterday, including an ‘entrepreneurial strand’. It states: ‘To be entrepreneurial in our culture is to see potential in existing and future activity and to translate that into enterprise for the benefit of wider society.’ Even allowing for the necessary blandness of organizational strategy statements, the notion of entrepreneurship has been entirely institutionalised: seeing potential and translating it into benefits. Having read Richard’s book I recognize a nativized term when I see one.

Unexplored terms, as Richard shows us, are freighted with their own politics. I agree, and these need to be unboxed. To be successful as an entrepreneurial community, here in an ‘Entrepreneurship Centre’, we will have to acknowledge the silences as well as the voices in that conversation, the exclusions as well as the inclusions. We need to understand what entrepreneurship means, not just to us, but to people who are not like us (that’s almost everyone!). That’s certainly a task for the anthropological method.

Is it, though, a job for anthropologists?

In other words, when it comes to the ‘why’ of Richard’s book, I’m almost convinced, but not quite. The book does [as another respondent, the anthropologist Daniel Knight, made clear] a great service within the discipline by attempting to rehabilitate entrepreneurship into something that can be taken seriously as an object of study in its own right. It therefore makes an important contribution within the tangled and political history of anthropology.

But I’m not a disciplinary anthropologist.

It seems to me that there is a significant and important social and intellectual contribution to be made by academics able to articulate an intellectually robust, useful, and engaged account of entrepreneurship that is neither excessively instrumental nor critical. This is, I think, where Richard is leading us, and I welcome that endeavour.

At the same time, as a management scholar and sociologist of markets I am inclined to side with Tett, not Pfeilstetter: the anthropological method is for everyone. And if the anthropologists have missed the entrepreneurial boat? Well, so it goes.

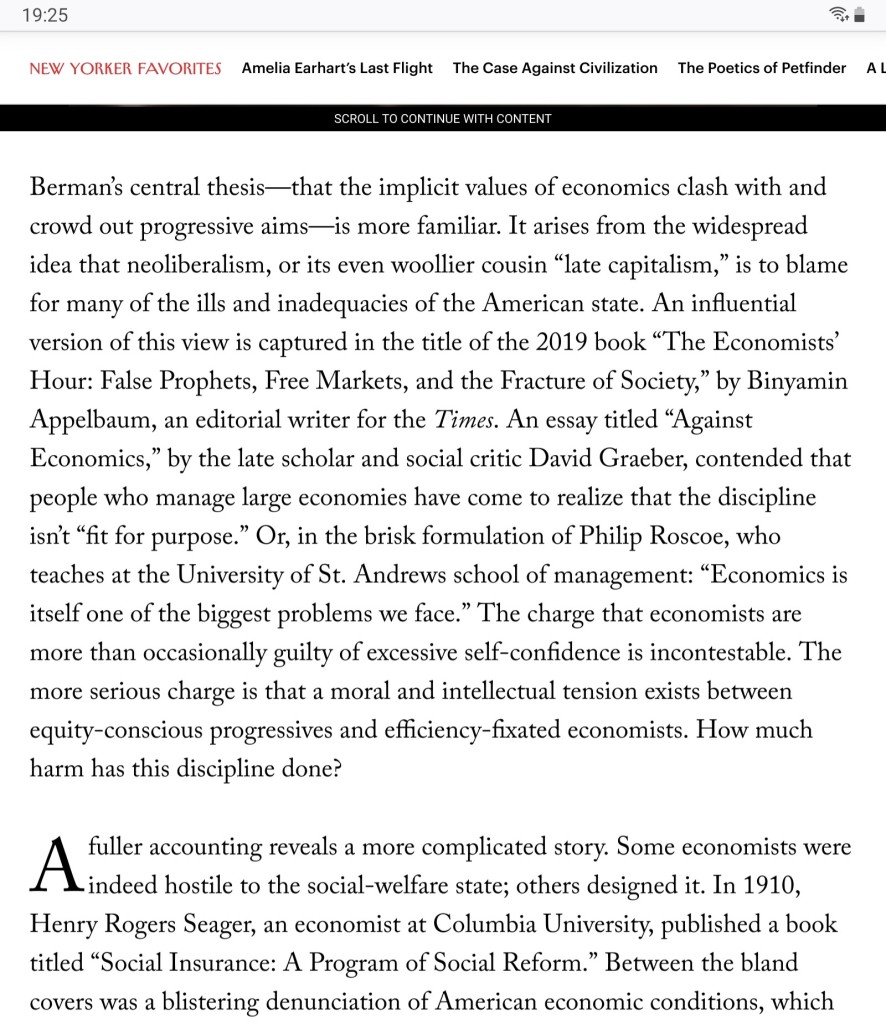

Mentioned in the New Yorker!

It’s not every day one is quoted – not just mentioned but quoted! – in a publication as eminent as The New Yorker, so you will forgive me for adding it to the scrapbook. The article, a review of Elizabeth Popp Berman’s new book ‘Thinking Like an Economist: How Efficiency Replaced Equality in US Public Policy‘ has me mentioned next to the late great David Graeber. We are the obligatory econ-hating-lefties in Idrees Kahloon’s ‘war on economics’ (see left) but still. I’m very glad to be in Graeber’s company, too.

The line itself comes from a blog I wrote for the LSE back in 2014, following the publication of my book I Spend therefore I Am (Viking, 2014, republished by Penguin as A Richer Life, 2015, and now available for less than a fiver, so knock yourself out). The book ruffled a few feathers among reviewers, just as Elizabeth Popp Berman seems to have done, and the blog was something of a reply to critics. Here it is:

How To Build a Stock Exchange: Making Finance Fit for the Future

Here’s my new project: a podcast! It’s titled How To Build a Stock Exchange: Making Finance Fit for the Future. It’s a story of stock markets and how they came to be so important in our world. It will feature my own work and showcase the research of the sociological studies of finance as it builds an account of the evolution of financial markets and their place in a responsible, sustainable future. I introduce it as follows:

Finance matters. We’re off to build a stock exchange, but first of all I’ll spend a little time explaining why financial markets matter. This episode explores how financial markets – a crucial mechanism for the distribution of wealth – are implicated in our present political malaise and looks at some of the ways that finance has squeezed us over the last three decades.

Episode One is called ‘Finance Matters and here’s how it starts…

A famous philosopher once said – ‘It is not from the benevolence of the butcher, the brewer, or the baker, that we expect our dinner, but from their regard to their own interest.’ It was Adam Smith, of course, born not far down the road from me in Kirkcaldy, Scotland, and the father of modern economics. He once walked to neighbouring Dunfermline in his dressing gown, apparently, so deep was he in thoughts, musings like this, and ‘Nobody but a beggar chuses to depend chiefly upon the benevolence of his fellow-citizens.’

From those words, published in 1776, a whole global order has sprung. We can call it capitalism, and at its centre lies a strange entity, so much part of our lives that we simply take it for granted.

I’m talking about the stock exchange…

You can find transcripts and audio here, or follow on iTunes, Spotify, or Stitcher.

More awfulness from the US labour market

Hot on the heels of my last review – of Ilana Gershon’s Down and Out in the New Economy – here’s a second offering for the THE on the subject of labour relations. This, from the esteemed philosopher Elizabeth Anderson, takes aim at the expansion of market logic into the private realm of firms, and the subsequent ceding of almost all power on the part of employees. In pursuit of a free-market, employers can hire – and fire – at will, and the results are quite shocking. Once again, Brexiteers beware: your much hoped for low-regulation world may have you, quite literally, pissing your pants at work. Here’s a taster:

Hot on the heels of my last review – of Ilana Gershon’s Down and Out in the New Economy – here’s a second offering for the THE on the subject of labour relations. This, from the esteemed philosopher Elizabeth Anderson, takes aim at the expansion of market logic into the private realm of firms, and the subsequent ceding of almost all power on the part of employees. In pursuit of a free-market, employers can hire – and fire – at will, and the results are quite shocking. Once again, Brexiteers beware: your much hoped for low-regulation world may have you, quite literally, pissing your pants at work. Here’s a taster:

“Elizabeth Anderson is a philosopher on the warpath. Her Tanner Lectures, published in this volume with comments and a response, take aim at the unelected, arbitrary and dictatorial power that employers, particularly in the US where labour laws are flimsy, hold over their work-forces. She calls it “private government”, in the sense that those governed – that’s us, by the way – are shut out of the governing process.

The book is littered with examples of firms that make employees’ lives a misery. The usual suspects are here and worse: I was shocked to discover that the right to visit the toilet during working hours has been a contentious and ongoing battle of American labour relations for many decades, and that it is not uncommon to be forced to wear nappies on the production line or urinate in one’s clothes…”

Read the rest here

Self as brand, Linkedin, and new ways of thinking about work

A recent review, for THE, of Ilana Gershon’s troubling Down and Out in the New Economy. It’s one of two books on labour relations in the United States I’ve reviewed of late – the other coming soon – and believe me, some of the material is shocking. Those of us subject to European labour regulations have no idea how lucky we have been (up till now, at least). Here’s the first couple of paragraphs:

‘Imagine a world without stable or secure jobs. A world where job seekers are told to embrace risk, to be flexible and upbeat, where the engine of the economy is powered by passion and lubricated by uncertainty. Such is the world of new-economy employment skilfully documented by Ilana Gershon’s sympathetic and wide ranging study.

For much of the 20th century, employment has been understood in Lockean terms of self-as-property with the worker renting her bodily efforts and skills for a prearranged period of time. Such a metaphor implies boundaries between work and personal life, and squabbles over such boundaries have been codified in labour law. In the new economy, says Gershon, we have come to talk about our jobs in a very different way. Interactions around work – job seeking, hiring, firing and quitting – are structured by a distinctive new metaphor that posits employment as business-to-business relationship. To be a business is to be a bundle of skills, assets and relationships, arriving at a new employer ready to deliver a particular service on a short-term, contractual basis. When we buy a service from a business we do not expect to invest in training or to have a long-term obligation once the service is being delivered. Gershon, a linguistic anthropologist, suggests that the change in metaphor underpins an important and unwelcome change in economic organization….’

You can read the rest on the THE website here

Evolution and organization, part 2: more sloppy language, dodgy organizational theory, and Weber being right all along

Spring is in the air. The sky is blue and the garden robin is lining his nest-box bachelor-pad with moss. At such a time the thoughts of man turn naturally, like those of the robin, to matters evolutionary, and in particular to the long-awaited second half of my blog on organization and evolution. I posted the first part before Christmas, though never made it to organization, waylaid instead by a lengthy detour into Richard Dawkins’ decidedly wonky metaphysics.

Pseudo-evolutionary chatter in organizations: it seems to be everywhere. We don’t bat an eyelid when Amazon talks about its ‘purposeful Darwinism’, a yearly cull of the worst performing employees. It doesn’t make us shudder to hear that this is based on constructive criticism offered to bosses via secret feedback mechanisms. Final year undergraduates cheerfully tell us about the ‘rank and yank’ mechanisms in the firms they hope to work for, never considering that things may not go to plan and they might themselves be yanked, not ranked.

Management scholars of a critical bent should be worried about this kind of thing, so I’ve set out to elaborate a genealogy of these ideas. It’s one of many possible lineages as the evolutionary tropes have themselves evolved and spread out in their own diasporic family tree; Continue reading “Evolution and organization, part 2: more sloppy language, dodgy organizational theory, and Weber being right all along”

The promise and paradise of austerity

Out online, my review of Martijn Konings’ The emotional logic of capitalism (Stanford University Press, 2015). Here’s an extract:

‘Certain questions dog progressive thought: why, in view of the manifest failures of financial capitalism, is its hold on our society stronger than ever? Why, despite the empirical evidence of foreclosures, vacant building lots and food banks are people unable to see the catastrophic consequences of current economic arrangements? How has neoliberalism emerged from calamity ever stronger (Mirowski, 2013)? Why, as Crouch (2011) puts it, will neoliberalism simply not die? With this slim book Martijn Konings, a scholar of political economy at the University of Sydney, sketches out an answer: that progressive understandings of capitalism have neglected its emotional logics – its therapeutic, traumatic-redemptive, even theological qualities – and failed to recognise our emotional investment in money, our belief in the social role of credit as an ordering, regulatory mechanism, and our need for the redemptive promise of austere, well-disciplined economy… ‘

‘Certain questions dog progressive thought: why, in view of the manifest failures of financial capitalism, is its hold on our society stronger than ever? Why, despite the empirical evidence of foreclosures, vacant building lots and food banks are people unable to see the catastrophic consequences of current economic arrangements? How has neoliberalism emerged from calamity ever stronger (Mirowski, 2013)? Why, as Crouch (2011) puts it, will neoliberalism simply not die? With this slim book Martijn Konings, a scholar of political economy at the University of Sydney, sketches out an answer: that progressive understandings of capitalism have neglected its emotional logics – its therapeutic, traumatic-redemptive, even theological qualities – and failed to recognise our emotional investment in money, our belief in the social role of credit as an ordering, regulatory mechanism, and our need for the redemptive promise of austere, well-disciplined economy… ‘

You can read the rest here

Cost-benefits and twitter follows: eleven weeks of good stuff, week 2

So far so good. It’s Sunday morning, the second week of January and I’m sitting down to write the second installment of my 11 weeks (or thereabouts) of good stuff. Each week I’ll take a section from the manifesto published in A Richer Life, and post it on this blog with some additional commentary.

As I review the not-very-inspiring viewer statistics for last week’s effort, here’s a supremely appropriate second extract:

And kick our cost- benefit habit. Efficiency is not the only virtue. A society needs justice, and empathy, with all the obligations that go alongside them. It’s too easy, faced with a difficult political decision, to emphasize benefits over costs and take refuge in ‘trustworthy’ numbers and scientific calculations. But when we examine those numbers, they turn out to be politics in disguise. We need conversation and debate over what is best, and best for whom, not what is cheapest; to open up the black boxes of measurements and metrics so that we can see what these metrics really are, and what they do. Cost-benefit thinking is corrosive in our own lives too. If we act only in anticipation of a return, we will all be the poorer, while a society where all contribute will be a far richer place. So go to that team meeting, even though it really isn’t part of your job. Take your friend/spouse/children to the play/film/concert, even though you’ll hate it; they’ll have fun and you may well find that’s enough.

The world has changed a great deal since the summer of 2014 when I wrote those words. The horrors of last year – Charlie Hebdo, our awakening to the ‘existential threat’ posed by Daesh, the attacks in Paris, and most of all, the refugee crisis in the Mediterranean and Europe – have forced a sudden maturing of political discourse. While economics still has plenty to say on the topic of migration – largely positive, as it happens – it is just one of many competing voices: the Christian left, for example, represented by Giles Fraser here, or the Archbishop of Canterbury’s careful association of British patriotism with welcome: ‘In today’s world, hospitality and love are our most formidable weapons against hatred and extremism’. Equally, there is an understandable fear, driven by the shadow of attacks that weren’t, and the ugly violence that manifested itself in Cologne on New Year’s Eve.

Closer to home, just look at the change in political discourse over flood defences. At the beginning of 2014 the coalition government demanded a great hike – a 60% increase in benefits – for every pound spent on flood defences. Following this winter’s deluge, we see the environment agency advocating a holistic approach to flood prevention, and stating ‘people will always come first’.

In fact, in such a climate, there is something appealing about the cool voice of reason provided by economic analysis – a dispassionate assessment of the long-term costs and benefits of any action. But it’s clear for now that there are bigger questions at stake.

We must be careful to distinguish between efficiency as a means of distinguishing between solutions to rival problems, and competing solutions to the same problem. In the latter instance, cost benefit has a lot to say. The problem comes in the assumption of transferability. An absurd example will illustrate the point: let’s say the cost benefit payoff of dealing with floods is better than that of dealing with refugees. There is an economic argument to say that we should sort out the floods first, whatever the human costs. That may sound crazy, but in debates over global warming, for example, it’s more or less what many economists have said. When an eminent American economist says that it’s unethical to invest in climate change prevention projects of uncertain return, one can’t help seeing a politics that privileges the haves of the developed world over the have-nots of those countries like Bangladesh.

But my book isn’t really about policy. I’m concerned about the corrosive effect that cost benefit calculations have on us as people – as persons. I argue that individually self-interested action, often driven by cost-benefit analysis, is collectively impoverishing. Private vice is not, despite what contemporary neo-Smithians like to say, a recipe for public virtue. Not at all.

Cost-benefit reasoning is a mode of thinking that we slip into very naturally, so naturally in fact that thinkers such as Daniel Dennet have argued it to be the only truly natural way of thinking. We are all its victims. Indeed, as I drag myself to my shed on a Sunday morning to write these words I can’t help noticing that the views of last week’s endeavour could be numbered on fingers and toes. Why on earth should I bother?

When I’ve finished the blog, I’ll announce it on twitter. I’m fascinated by the economics of twitter, and particularly the cost-benefits of following others. Being a twitter dilettante (a twittertante? A dilettwit?) I just drop in now and then to see what’s going on, catch up on the news and so forth. My friend and fellow twitterante @cfhelgesson captures the mood of this social media existence nicely when describes his news feed as being like rain: when he’s thirsty he can cup his hands and take what he wants, and when he’s not it simply passes by.

A diletwit like me can only cope with following a couple of hundred accounts, beyond which there is a ‘diminishing marginal return’ on each additional follow. (CF, more industrious than I, follows over 700. I will ask him how he does it.) Thus I am operating a clear-cost benefit algorithm for managing my twitter follows; the costs in terms of missed tweets and time required imposed by following one more person outweigh the potential benefits in terms of hilarity, news, political acumen, feline cuteness and so forth. It’s one in, one out, pretty much.

How then do people rack up 10,000 follows? Surely the cost of keeping up with each of these additional follows will greatly outweigh any infinitesimal marginal benefit? Unless, of course, the game is different; if a user is only interested in building up his or her own following, then the economics suddenly work out very well. There is no cost in any additional follow because one has no intention of paying any attention to anything they do, nor is there a cost for any additional follower. But if one sees value in a huge following the marginal return on each follower is increasingly large. The whole economy is suddenly upside down. (The same applies, oddly, to the business of being super rich. When one is wealthy enough to start buying yachts, football clubs and politicians, each extra dollar becomes worth a whole lot more than the last one.)

If one follows total strangers in the expectation that some of them will follow you back, then following huge numbers is an efficient and instrumental means of generating value, and ‘building an online platform’ as the marketers like to say. I was followed last week by ‘a self-taught photographer and photoshop artist located in Los Angeles’ who tweets gorgeous head shots and theatrical bon-mots to an audience of 11,000, but follows 9,999. Including me. Enough said.

Presumably, not everyone follows back, and that 9,999 number requires careful curation. 30,000 follows to 10,000 followers might look bad; better to keep it level. So every time I encounter a twitter profile following a four figure number, or more, and a matching level of followers I think ‘Aha!’

I’m sure anyone with any level of sophistication regarding social media figured this out long ago – but on the other hand, if they did, why does the following trick still works at all? (Maybe it doesn’t – maybe there is, across twitter, a diminishing marginal return on following for followers. That would be truly ironic.)

I instinctively dislike this game. There are two ways of approaching twitter. The first is as a community, where one can share jokes and articles, strange gifs and pictures of cats and all the other things that make the Internet go round. The emphasis, though, is on share, because sharing implies receiving and participating as well as giving. It involves a certain degree of empathy in as much as one expects that people may be interested in whatever it is that one has chosen to tweet. It involves treating people as worth something in them themselves.

The second is to treat twitter as a gigantic tool for self-aggrandizement: building an online profile, getting famous, driving business, ultimately cashing in. It involves asking people to pay attention to you – to spend their time, their efforts on you – without any sense that you will pay attention in return. That additional follow, your ten thousandth, is a trick, a con. It is a message sent to someone saying ‘Hey, you’re interesting…’ that means no such thing.

Of course, if cost benefit is your only measure of moral purpose, then such a game is completely legitimate. It’s a cheap and easy way to hoover up followers, and you’d be a fool not to. That’s why cost benefit alone is such a damaging moral standard, because it mandates instrumental and collectively impoverishing courses of action. The twitter following game is a synecdoche for a much bigger discussion: we need ways of talking and thinking that transcend cost benefit in our own private lives as much as our public sphere. If everyone behaved according to the rules of the twitter following game in real life, we really would have some problems.

All of which brings me back to the business of writing this blog. If I were driven by cost benefit alone I would have sat in the warm and read the paper, pausing only to follow a few more hundred total strangers. I certainly wouldn’t have spent a precious Sunday morning hunched in the shed, peering at the screen, tapping out words while my toes go steadily numb.

I’d like it to be read, of course. I’d like the number of readers to exceed the number of my fingers and toes (so if you like it, please pass it on!). But that’s not why I wrote it. I did so because I said that I would, and I have a promise to keep to myself as much as to the invisible Internet. I did so because I know some people –CF, perhaps – will read it, and I hope they will like it. Perhaps it will raise a smile here and there.

And finally, I did so because I consume blogs too, many of them very good, and I want to be a genuine part of that community of writers and thinkers. I don’t expect this blog will make me rich and famous, and I’m not building an online platform; I simply believe that the world is a better place for the collective effort of writing decent prose and sticking it online. Because lots of us think that, it is.